“It's your f***ing site, too!”

At a former employer, my Vice President of Engineering and Operations had a reputation for his language. He also had a reputation for his deep passion for things like site availability, incidents, downtime, and almost anything related to making sure the company's website was up and running, and especially that the end users were having a good experience using it.

So whenever he saw or noticed something that made him question whether anyone else's dedication to users was any less than his, you would certainly know it.

To him, if you found an "Easy Button" to make an outage disappear, it was likely only going to be a temporary fix. Reliability would be a proportionate and direct result of the effort teams and individuals put in to achieve it. When we experienced an outage our team/company was fortunate (or unfortunate, depending on your perspective) enough to be able to simply "throw money at the problem", often by horizontally scaling our infrastructure, until we were able to determine a legitimate root cause and implement a fix. Once we pushed the fix, we'd try to normalize our infrastructure back to where it was before. Sometimes it worked - sometimes it didn't. But the effort never stopped, and it was hardly ever easy.

Downtime is expensive, and sometimes math is hard

I once worked at a place (We'll call Company X) where we had some pretty bad outages. It got to a point where there were internal jokes that to take our user base, all our competitors had to do was start a marketing campaign that said:

"We're just like Company X, except we work."

In the industry, availability is often measured and reported by "the number of 9's" your site is available. The term "available" is sometimes subjectively defined (and sometimes the calculation is, too), but the gist of the Uptime or Availability metric is to measure and report the number of minutes (or hours) of downtime your service or site has experienced. Cloud service companies report and define Service Level Agreements to their customers where if the service availability drops past a certain threshold for a given time window, the customers would be entitled to a chargeback, which could be a significant amount of money. Additionally, if your own services are down, there's a high chance that the incident is costing your company money or revenue. Various companies have shared that downtime can cost them anywhere from +$10,000 to +$200,000 per minute of downtime.

In general, availability is calculated by taking the number of minutes your services were unavailable for a given time range, and dividing that number by the number of total minutes within that same time range.

If you had 3 incidents in the month of March that resulted in 30 minutes of downtime:

If your incidents total between 5 and 8 hours of total downtime for the last twelve months, for example, you could claim to have "Three-nines" of availability (~99.9%) over the past year. For some companies, one incident can last 5-8 hours, though. Based on this math, companies who claim "Two-nines" over a year's time clearly have a lot to improve on, as that calculates to +87 hours of downtime for the year. You can imagine that multiple incidents (especially longer lasting ones) could destroy a company's availability numbers.

| Availability | Downtime / Year | Downtime / Month | Downtime / Week | Downtime / Day |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 99.999% | 5.256 Minutes | 0.438 Minutes | 0.101 Minutes | 0.014 Minutes |

| 99.990% | 52.56 Minutes | 4.38 Minutes | 1.011 Minutes | 0.144 Minutes |

| 99.950% | 4.38 Hours | 21.9 Minutes | 5.054 Minutes | 0.720 MInutes |

| 99.900% | 8.76 Hours | 43.8 Minutes | 10.108 Minutes | 1.440 Minutes |

| 99.000% | 87.6 Hours | 7.3 Hours | 101.08 Minutes | 14.4 Minutes |

Table 1: Availability Calculations

Downtime is no fun

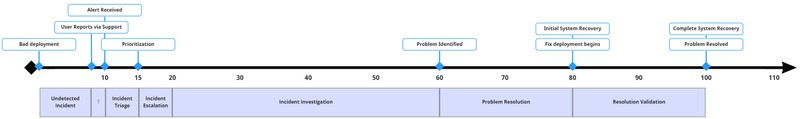

Ideally, incidents follow a distinct level of expectations. We plan for the flow of events to be very linear in nature, from when an incident begins, to when the escalations happen, to the actual resolution.

Image 1 - What an ideal incident timeline could look like

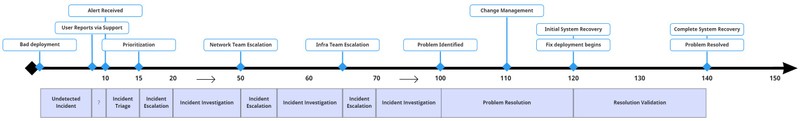

Quite often, this isn't the case, and sometimes, there are a lot of circular (almost recursive) events - especially with alerting, paging, and escalations. This can drive up the Time to Resolution significantly, especially for folks who haven't developed the Oncall "muscle memory" that other more seasoned team members may already have.

Image 2 - How an actual incident timeline could look like

From setting up alerts, thresholds, runbooks, escalations, and trainings, then going through incidents, on-call rotations, post-mortems, root-cause-analysis, and action items - incidents, operations, and problems are a time sink, and as a result, maintaining uptime and availability are also time sinks.

But what if I told you that a lot of that incident downtime could be avoided? What if there was an easy button, or a magic wand that your CTO could wave to make on-call life something to look forward to?

Spoiler alert: There isn't.

There is NO "Easy Button"

Being in the reliability space, I have often come across teams who are looking to buy a tool, or implement a practice, and expect a "Jack and the Magic Beanstalk" overnight event to increase their availability metrics and claim a win. To be fair, sometimes they get sold on that dream.

"Buy this tool, install it, set it, and forget it. Instant Reliability! SO EASY!"

Then the reality sets in: You can't just buy a 9.

Practices like Load/Performance Testing and Reliability/Chaos Engineering, are great when they have tangible data that you can improve on. Obviously you need to install and use the software, but you also need to spend time analyzing the results, then desiging and implementing strategies to improve the outcomes. Projects that try to make things as easy as possible certainly exist. k6, for example, is a very simple and easy to use product for load and performance testing. The open source project is free, and installs within seconds. So you're not even buying anything. There's even a chaos engineering extension. Instant reliability, right?

Anyone within the testing realm can tell you it's not as easy as it sounds. Designing, generating, and executing tests and experiments from within the k6 platform is very simple and repeatable, for example. But that is not all that needs to happen. You'll need to analyze and understand metrics and events that are generated from your tests, and then implement improvements in order for there to be any long-term value from your time spent.

Assuming you already know what metrics and events you're trying to be aware of, there's still alert tuning, escalation timing, performance and regression testing, resilience experiments, gamedays and fire drills, runbook audits - and that's assuming you're just spending this kind of effort in your production environment. A testing or pre-prod environment could at least double the effort and cost. These are all events that get rolled into the proactive mindset of folks who may not look forward to being on-call, but certainly helps them be more at ease when their scheduled rotation comes up.

If you don't know what metrics and events you're trying to be aware of, there's all that stuff above, plus the effort of discovering which services emit which metrics, whether or not those metrics are even useful to you, and then instrumenting metrics that you've learned aren't available yet.

None of these events are things that happen once or twice, or even just quarterly. They are recurring events that continuously occur (either automated or manually organized) that help reduce the toil of incidents, and in the long run reduce the costs of downtime.

What I am recommending is not a mind-blowing or revolutionary idea. Scaling your reliability practice is not as simple as throwing money at the problem. Buying/using the right tools and hiring the right people are only a part of the solution. Only doing these steps ends up contribuitng to added technical debt, not giving enough attention to matters that need it the most. Teams need to be given time to "do things the right way". If the end goal is to improve your availability by "another 9" (or even a fraction of a 9), that goal is achieved through various iterations of improvements over time. Teams that invest the time to address and utilize their tooling properly and consistently wil have lower amounts of downtime, and lower costs due from downtime as a result. My SRE teams took a lot of ownership and pride in improving the availability of our various services. We spent the time and effort to define, measure, analyze, and improve the availability and uptime of our sites... because it was our f***ing site, too.